Solving Australia’s food waste problem requires purposeful planning

Australia has a food waste problem. According to the National Waste Report 2020, we generated more than five (5) million tonnes of it in 2018-19.

Food waste has a big impact. When we throw away food, we not only waste money but the natural resources that go into producing it. At a time when the finite boundaries of our planet are under stress, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions are rising, and food security is growing for millions around the globe, food waste must stop.

Currently, food charts a linear path from production through to consumption, with food and organics lifecycle management in Australia focused largely on end-of-pipe solutions. Data from the National Waste Report shows that of the 14.3 million tonnes of core organic waste[1] generated in Australia in 2018-19, 48% went to landfill. This figure is higher still for food waste specifically, of which 74% was landfilled.

Improving food and organic waste management involves phasing out the linear food system – and it’s a key part of our transition to a circular economy, where ‘waste’ is designed out.

At the global level, this approach is enshrined in the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development under Goal 12: Responsible Consumption and Production, and there are new schemes for avoiding food waste sprouting up in cities around the world [read about some of these in part one (1) of our series on food waste].

When it comes to tackling food and organic waste in Australia, target six (6) of the National Waste Action Plan aims to halve organic materials sent to landfill by 2030. Arguably, this is an end-of-life target that embodies the linear food management approach. The desire to improve food and organic material management is growing, with the national conversation moving towards how we embrace a more circular food system and ‘FOGO’ (Food Organics Garden Organics) being the buzzword on everyone’s lips.

In good news, states and territories are continuing to plan for and roll out local government FOGO systems, and the federal government has jumped on the bandwagon, providing support through its recently released $67 million Food Waste for Healthy Soils Fund. The initiative, which will require co-contributions from participating jurisdictions and industry, aims to increase Australia’s organic waste recycling rate from 49% to 80% by 2030 through building FOGO infrastructure and fostering a regenerative approach to food systems that returns the nutrients embedded in recycled organics to our soils.

The importance of planning for organics

As with all steps involved in the transition to a more regenerative food system and the circular economy in general, setting up an effective, long-term organics system requires integrated planning.

For example, household FOGO schemes must have four (4) integrated components in order to be successful. The first is MSW[2] kerbside collection infrastructure and services for source separated food and organic materials (including garden waste). Secondly, these must be accompanied by clear and consistent communication to educate households on what can be accepted in the FOGO bin. The third component involves recycling and repurposing these organic materials – often as compost, or for energy generation via anaerobic digestion. The fourth element underpinning all of this (and clearly informing the education program) is the regulatory regime that enables the recycled organic material to be returned as a raw material for beneficial re-use such as applying compost to agricultural land. This regulatory framework also protects the environment and community by ensuring that materials are reused safely by, for instance, meeting an agreed standard

For FOGO to succeed and have true impact, it must sit within an overarching, state-adopted waste and resource recovery or organics strategy – one that firstly prioritises higher order material management actions across the supply chain, such as avoiding and minimising food and organic waste. Behavioural campaigns such as WRAP UK’s Love Food, Hate Waste, which has been adopted in some Australian jurisdictions, are key to achieving these higher order objectives. Incentives and other pathways for businesses to redistribute unsold produce to food banks are also important. The avoidance priorities underpinning such initiatives are outlined by the waste management hierarchy.

Regulatory frameworks are required to provide clear pathways for reclassifying FOGO and FOGO-derived materials as a resource permissible for beneficial reuse, such as applying compost to agricultural land. They also protect the environment and community by ensuring that materials are reused safely by, for instance, meeting an agreed standard. Such frameworks serve as the basis for educating households about inputs into kerbside FOGO – for example, is ‘compostable’ packaging in or out? The regulatory certainty provided by these frameworks is also essential in fostering markets for FOGO end products.

Additionally, FOGO is not just about MSW[2] generated by households. Avenues for business participation in FOGO are important for capturing additional value from C&I[3] waste streams, and for the biggest impact as well as to maximise opportunities, organic material management should consider the entire supply chain.

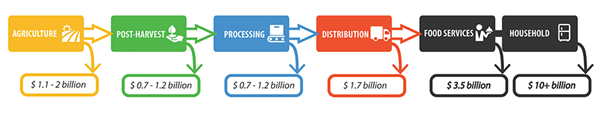

Australia’s National Food Waste Baseline Report (against which progress towards our national food waste reduction targets is tracked) reveals that by weight, almost as much food is lost in primary production as at the household level: ~2.3 vs. ~2.5 million tonnes. Data from Fight Food Waste CRC similarly indicates that by value, financial losses from food waste are a significant issue across all points of the entire supply chain.

Source: Fight Food Waste CRC

The benefits of addressing food and organic waste through such an approach are myriad – we can reduce GHG emissions, conserve resources and ease pressure on ecological systems, lower household and business costs, reduce food insecurity, conserve dwindling landfill space, create new sustainable industries and jobs, and improve soil quality to enhance the agricultural lands that produce our food in the first place.

Introducing FOGO without careful, holistic planning risks not only squandering many of these opportunities, but locking in less sustainable, linear food production and consumption pathways.

As noted above, the federal government has ambitions to put FOGO to productive use on agricultural soils by converting it into high-grade compost and has supported this very worthy cause through its Food Waste for Healthy Soils Fund. However, a significant portion of the fund will go towards state-based infrastructure projects, yet many states and territories are not ready to scale up their FOGO processing capacity – nor should they necessarily rush to, given the importance of focusing on avoidance first.

A snapshot of where Australia’s states and territories are at in their respective FOGO journeys can be downloaded here.

Hasten carefully - the consequences of rushing to build

Building FOGO infrastructure without proper planning that considers the local context can have unexpected and undesirable consequences. Alongside case studies that bode well for Australia’s prospects of beating food waste, there are cautionary tales.

In the UK, the District Councils’ Network has spoken out against the planned national roll out of a garden waste (GO) collection program. Representing 183 local councils, the Network warns that this service will cost taxpayers £2.5 billion (~A$4.65B) over seven (7) years. These services will be of little benefit, due to the negligible size of garden organic waste streams in the red bin for many households, particularly in medium- and high-density urban areas.

This story highlights that one size does not fit all when it comes to FOGO and related schemes. Instead, FOGO planning must consider actual streams and volumes, based on local demographic factors. For many local government areas represented by the District Councils Network, where residential areas often feature high proportions of MUDS [4] with small backyards and thus negligible garden waste, GO collection is largely inappropriate and unnecessary.

In Australia, where there are large volumes of food and organic waste, building FOGO processing infrastructure now instead of focusing on avoidance will see us continue down the linear organic management path. Under this linear approach, FOGO processing can be framed as a major investment opportunity; for example, the Clean Energy Finance Corporation (CEFC) recently noted that the transition of metropolitan areas to FOGO schemes will require the construction of an additional 880,000 tpa[5] of composting and anaerobic digestion capacity.

However, if we genuinely want to move towards a circular economy, designing out waste in the first instance – and driving down organic waste stream volumes – must be the priority. Governments and investors looking to build new infrastructure must therefore always keep in mind the goal – and future achievement – of reducing organic waste volumes. This will avoid the creation of stranded assets that may otherwise result from rushing to scale up FOGO processing capacity.

Making the Healthy Soils Fund work: overseas inspiration

Government proponents claim the Healthy Soils Fund takes a “plate to paddock” approach. However, under its current grant structure – in providing funding for infrastructure only – the fund overlooks an important opportunity to help foster sustainable production and consumption behaviours, as well as the regulatory pathways that are foundational to long-term circular food and organic waste management.

The European Union’s Farm to Fork strategy is a pioneering example of a holistic, entire supply chain approach to tackling food waste that could be applied to Australia’s Healthy Soils Fund. Part of the European Green Deal, Farm to Fork takes a systems-level approach towards improving the health and sustainability of food production and consumption.

Source: European Commission

Such systems-level approaches to reducing organic waste will not only reduce economic losses and reduce emissions, but unlock green growth and economic opportunities.

Tweaking the structure of the Healthy Soils Fund to allow it to support and encourage careful organic planning by states by offering funding opportunities for the more foundational aspects of FOGO – such as avoidance campaigns, regulatory frameworks, and so on – would help catalyse this systemic shift.

Then, to turn Australia’s circular food system ambition to action, governments can look to the outcome of FIAL’s Feasibility Study: a clear roadmap for reducing food loss and waste towards an overall 52% reduction in organic waste by 2030.

The roadmap involves rolling out 23 interventions that target all stages of the supply chain and focus on the priority goal of waste avoidance through three (3) types of actions: behavioural change campaigns, policy interventions such as legislation and regulation to unlock private sector action, and industry-driven initiatives such as voluntary agreements.

Importantly, this is not a list of ‘pick and choose’ interventions. The components of FIAL’s roadmap are interdependent and designed to function as one whole. As such, the success and outcomes of each individual intervention depends on the roll out of the roadmap in its entirety.

While the systems thinking involved in implementing circular approaches to food and organic material management involves a paradigm shift, the benefits of pursuing this transition speak for themselves: implementing FIAL’s roadmap has the potential to avoid the release of more than 50 million tCO2e[5] and deliver a $58 billion return on investment – with further benefits for the economy, the environment and entire Australian community.

-----

[1] Core organic waste is primarily food organics, garden organics, timber and biosolids

[2] MSW = municipal solid waste

[3] C&I = commercial and industrial waste generated by commercial, industrial, government, public or domestic premises that is not collected as Municipal Solid Waste

[4] Massachusetts, for example, legislated a disposal ban on commercial organic material in 2014 that requires organisations producing certain volumes of organic waste to implement diversion and recycling systems.

[5] tCO2e = tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent